*English below

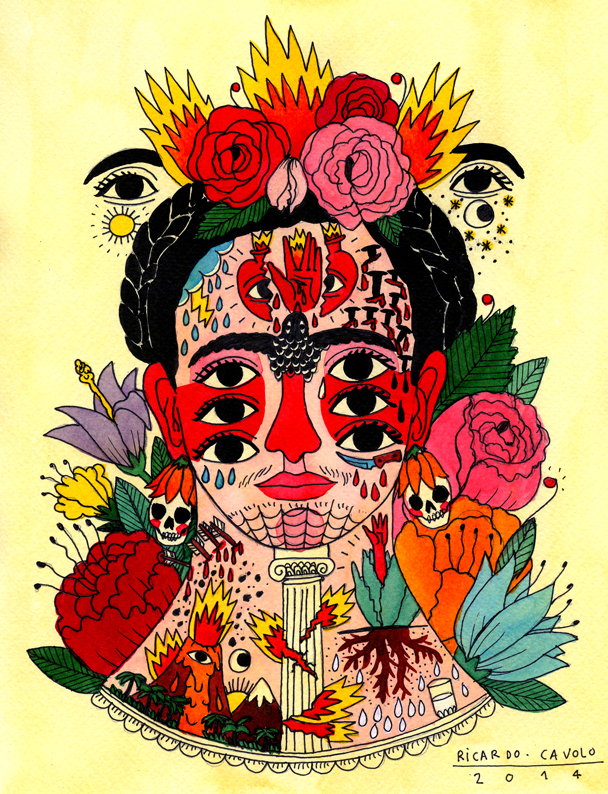

Δεν είναι εύκολο να σταθείς μπροστά σε έναν πίνακα Μπαρόκ, χωρίς να νιώσεις μικρά ρίγη να σε διαπερνούν βραδέως. Οι έντονες αντιθέσεις φωτός-σκιάς, οι απότομες κινήσεις των μορφών που προκαλούν συσπάσεις, οι πολύπλοκοι διαπλεκόμενοι όγκοι και η μεγαλειότητα των μορφών, διεγείρουν τα νευραλγικά εκείνα σημεία της νόησης και της συναίσθησης, που τις περισσότερες φορές αποφεύγουμε να επικαλεστούμε. Πολύ περισσότερο, προκαλεί η θεματολογία, που ξεχειλίζει από αφηνιασμένα συναισθήματα, μονίμως υπερβολικά. Το δράμα, η έντονη θεατρικότητα, ο ψευδαισθητισμός είναι λίγα από μία πλειάδα έντονων χαρακτηριστικών, που δικαίως το κατέστησαν ένα από τα πιο ιδιόρρυθμα καλλιτεχνικά ρεύματα. Οι καλλιτέχνες του 17ου αιώνα, στόχευαν στη συγκινησιακή επιφόρτιση του πνεύματος, μέσω ενός σχετικά «ευανάγνωστου» πίνακα. Και το κατάφεραν, δημιουργώντας στον θεατή το αίσθημα, πως οι ανήσυχες φιγούρες διακατέχονται από έναν κόσμο ηθικών ανομημάτων, χωρίς αυτά να είναι καταδικαστέα. Το είδωλο του αναγνώστη, αντικατοπτρίζεται ενδόμυχα στις εκρηκτικές αναπαραστάσεις.

Ξεκινώντας από την ίδια την ονομασία του ρεύματος, οι ρίζες της λέξης Μπαρόκ, προέρχονται από το πορτογαλικό barocco, που σημαίνει ανώμαλο μαργαριτάρι. Η περίοδος της Αναγέννησης, που επανέφερε το λησμονημένο φως μετά τον Μεσαίωνα, «δεν μπορούσε» να ακολουθηθεί από κάτι «σκοτεινό». Το Μπαρόκ όφειλε να παραμεριστεί, να μην ανθίσει και να αφήσει το κίνημα της Αναγέννησης, να εξαφανίσει κάθε «μελανό» σημείο των Σκοτεινών Χρόνων. Οι τεχνοκριτικοί του 17ου αιώνα, μετέτρεψαν τη λέξη σε baroque, γαλλιστί, θέλοντας υποτιμητικά να χαρακτηρίσουν το νέο καλλιτεχνικό στυλ, ως κάτι παράδοξο και ιδιόρρυθμο, το οποίο αναίσχυντα, παραγνώριζε τους αυστηρούς κανόνες της κλασικής τέχνης, που για τους ιδίους μεταφραζόταν σε μία οικτρή έλλειψη καλαισθησίας. Παρ’ όλα αυτά, το «ανώμαλο μαργαριτάρι», βρισκόταν κάπου στο ενδιάμεσο. Λαμβάνοντας υπόψη, πως τα καλλιτεχνικά ρεύματα έχουν ανάγκη να εκφράσουν το γίγνεσθαι της εποχής τους, τότε το «κιαρόσκουρο» Μπαρόκ, εξέφραζε τις εξελίξεις και τις αντιφάσεις της εποχής. Η εναλλαγή φωτός-σκιάς αποτυπώθηκε στον καμβά, ακριβώς επειδή κυριαρχούσε παντού. Από την πολιτική ως τη θρησκεία, η κοινωνικοποίηση μέσα από την συνύπαρξη των άκρων, απέδιδε μία ατέρμονη συγχώνευση δραματικών αρετών: από τον μυστικισμό στον ρεαλισμό κι απ’ τον ερωτισμό στον ασκητισμό. Η αντιμαχία που βίωσε η Ευρώπη της Μεταρρύθμισης και της Αντιμεταρρύθμισης, δημιούργησε καλλιτεχνικά στρατόπεδα, με το Μπαρόκ να επιστρατεύεται στον αγώνα της Ρωμαιοκαθολικής Εκκλησίας. Η αμεσότητα των μορφών, η επιβλητικότητα των κτηρίων, η απλούστευση των θεμάτων προκαλούν τη συναισθηματική συμμετοχή του θεατή, δίνοντας την αίσθηση πως η Καθολική Εκκλησία ανοίγει τα μπράτσα της για να αγκαλιάσει τους πιστούς.

Καραβάτζιο, Ρούμπενς, Τζεντιλέσκι, Ρέμπραντ, Μπερνίνι, Βερμεέρ, Μοντεβέρντι. Από τη ζωγραφική έως τη μουσική, οι εκφραστές του καλλιτεχνικού αυτού ρεύματος, έχουν ένα κοινό: αποστρέφονται τους κλασικούς κανόνες της ομορφιάς. Αγαπούν τη φυσική αναπαράσταση, κινούνται στο πρίσμα της νατουραλιστικής απόδοσης. Εγκαταλείπεται η ωραιοποίηση των μορφών, η ιδεαλιστική απεικόνιση των τοπίων καθώς και τα «μεγαλειώδη γεγονότα». Η φυσική αμεσότητα της απεικόνισης, υπερέχει του ιδανικού. Ο Καραβάτζιο, αποδίδει τον Άγιο Παύλο στον πίνακα «Η μεταστροφή του Αγίου Παύλου» ως άξεστο Ρωμαίο στρατιώτη ενώ τον χωρικό ρυτιδιασμένο και φαλακρό. Οι αυτοπροσωπογραφίες του Ρέμπραντ, στερούνται οποιουδήποτε ωραιοποιημένου χαρακτηριστικού, με τέτοιο τρόπο που η εγκατάλειψη αναζήτησης του «όμορφου» αφήνει χώρο στην αποτύπωση της ειλικρίνειας. Οι γυναικείες φιγούρες στους πίνακες της Τζεντιλέσκι, δεν θυμίζουν σε τίποτα τις γλυκές και άκακες «αιθέριες υπάρξεις» της Αναγέννησης, πόσο μάλλον παρουσιάζουν το πρόσωπο εκείνο που η εποχή καταπιέζει και αποτρέπει να εκφραστεί. Πονάνε, αντιδρούν, εκδικούνται, εναντιώνονται. Από την άλλη οι γυναίκες του Βερμεέρ, είναι «ασήμαντες». Μία μαγείρισσα, μία τεμπέλα υπηρέτρια, μία τροφός και μία άγνωστη κοπέλα με μαργαριταρένιο σκουλαρίκι, έως τότε δεν αξιώνονταν απεικονίσεων. Το Μπαρόκ τις αναδεικνύει, τους δίνει υπόσταση, τις εξυψώνει. Τα τοπία του Μπρέγκελ, δεν εξαίρουν το εσωτερικό κάποιας εκκλησιαστικής σκηνής ή κάποιας αριστοκρατικής οικίας, αλλά την καθημερινότητα και τις λαϊκές παραδόσεις, παρουσιάζοντας την παράδοξη ανθρώπινη πραγματικότητα. Η όπερα «Ορφέας» του Mondeverti, εγκαταλείπει τους δογματισμούς της σύνθεσης και χρησιμοποιώντας για πρώτη φορά άμεση μουσική γλώσσα, συγκινεί και εγείρει τον συναισθηματισμό, μετατρέποντας μία πέρα για πέρα ελκυστική μουσική.

Το Μπαρόκ, άνθισε στις αρχές του 17ου αιώνα και παραχώρησε τη θέση του στο Ροκοκό στα μέσα του 18ου. Μέχρι τότε όμως, είχε καταφέρει να εξυψώσει την ανθρώπινη υπόσταση, μέσα από τα πάθη και τα συναισθήματά του. Προκάλεσε τον θεατή να συμμετάσχει, να ταυτιστεί, να αντιληφθεί την ψυχική ή συναισθηματική κατάσταση των απεικονιζόμενων. Μετέτρεψε τον άνθρωπο από μονάδα, σε μέρος του συνόλου, αποτυπώνοντάς το, σε όλες τις τέχνες.

Baroque: The “Irregular Pearl” of the 17th century

It’s not easy, standing in front of a Baroque painting without feeling small tremors on the inside. The intense contrast between light and shadow contrasts, the abrupt movements of figures that cause contractions, the complex intertwined bulks and the majesty of figures, stimulate those neuralgic points of the mind and consciousness, which we often try to avoid. Much more invoking, are the themes that are overflowing with permanently rampageous emotions. Drama, intense theatricality and illusionality are a few of a plurality of strong features, which justly made Baroque one of the most peculiar artistic movements. The artists of the 17th century, aimed at attributing emotional spirit, through a relatively “readable” painting. And they succeeded in generating the viewer’s feeling that the restless figures, possessed by a world of moral transgressions, yet without them being condemned. The reader’s image inwardly reflects in explosive representations.

The name of the movement itself, the roots of the word Baroque, derives from the Portuguese barocco, which literally means an “irregular pearl”. The Renaissance period, which reinstated the forgotten light after the Middle Ages, “could not” be followed by something “dark”. The Baroque was to be casted aside, not flourish and let the movement of the Renaissance, eliminating the all “black” point of the Dark Ages. The critics of the 17th century, turned the word into baroque, in French, wanting to negatively characterize the new artistic style as something strange and peculiar, which shamelessly ignored the strict classical art rules, the same rules which for them translated in a deplorable lack elegance. Nevertheless, the “irregular pearl”, was somewhere in between. Considering that the artistic currents need to express the broader scene of their era, the “chiaroscuro” Baroque, expressed both the developments and contradictions of it. The light and shade switching, was imprinted on the canvas just because it did prevail. From politics to religion, the socialization through the coexistence of extremes yielded endless merger dramatic virtues: from mysticism to realism and from eroticism to asceticism. The confrontations experienced by Europe of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, created artistic camps, with Baroque conscripted to fight in the Roman Catholic Church. The immediacy of the figures, the majesty of the buildings, the simplification of the issues causing the emotional involvement of the viewer, giving the impression that the Catholic Church opens its arms to embrace the faithful.

Caravaggio, Rubens, Gentileschi, Rembrandt, Bernini, Vermeer, Monteverdi. From painting to music, the exponents of this artistic current, have something in common: they averse the classic, stereotypical standards of beauty, the love towards the native representation and they “move” inside the prism of a naturalistic output. They abandon the beautification of their figures, as well as the idealistic depiction of landscapes and the “grand facts”. The natural immediacy of imaging excels the ideal. Caravaggio pictures St. Paul in “The conversion of St. Paul”, as a crass Roman soldier while the villager is presented as wrinkled and bald. Rembrandt’s self-portraits lack any beautified attribute, in a way that the abandonment of “beauty”, eventually leaves space for sincerity to be imprinted. The female figures of Gentileschi do not resemble sweet and harmless “ethereal beings” of the Renaissance. On the contrary, they present the era’s face of oppression and prevention of expression. They hurt, react, retaliate, oppose. On the other hand, the women of Vermeer, are “insignificant”; a cook, a lazy maid; a nurse and an unknown girl with a pearl earring, were until then not worthy of being illustrated. Baroque highlights them, it gives them status, it uplifts them. The landscapes of Bruegel do not praise the inside of a church, or some aristocratic house, but everyday life and folk traditions, presenting the paradoxes of human reality. “Orpheus”, Monteverdi’s opera, abandons the dogmas of composition and uses a direct musical language that moves and raises sentimentality, rendering it utterly appealing.

Baroque flourished in the early 17th century and gave way to the Rococo in the mid-18th century. Until then, the movement had managed to elevate the human existence through its very own passions and feelings. It dared the audience to participate, to identify with and understand the mental and/or emotional state of the depicted. Baroque transformed the human being from a single unit to a piece of the whole, imprinting and reflecting it, in all art forms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.