A new interpretation of the oil painting by creating three-dimensional strokes. This technique allows the viewer to visualise the work in a three-dimensional space and to explore each stroke with a deeper feeling.

A new interpretation of the oil painting by creating three-dimensional strokes. This technique allows the viewer to visualise the work in a three-dimensional space and to explore each stroke with a deeper feeling.

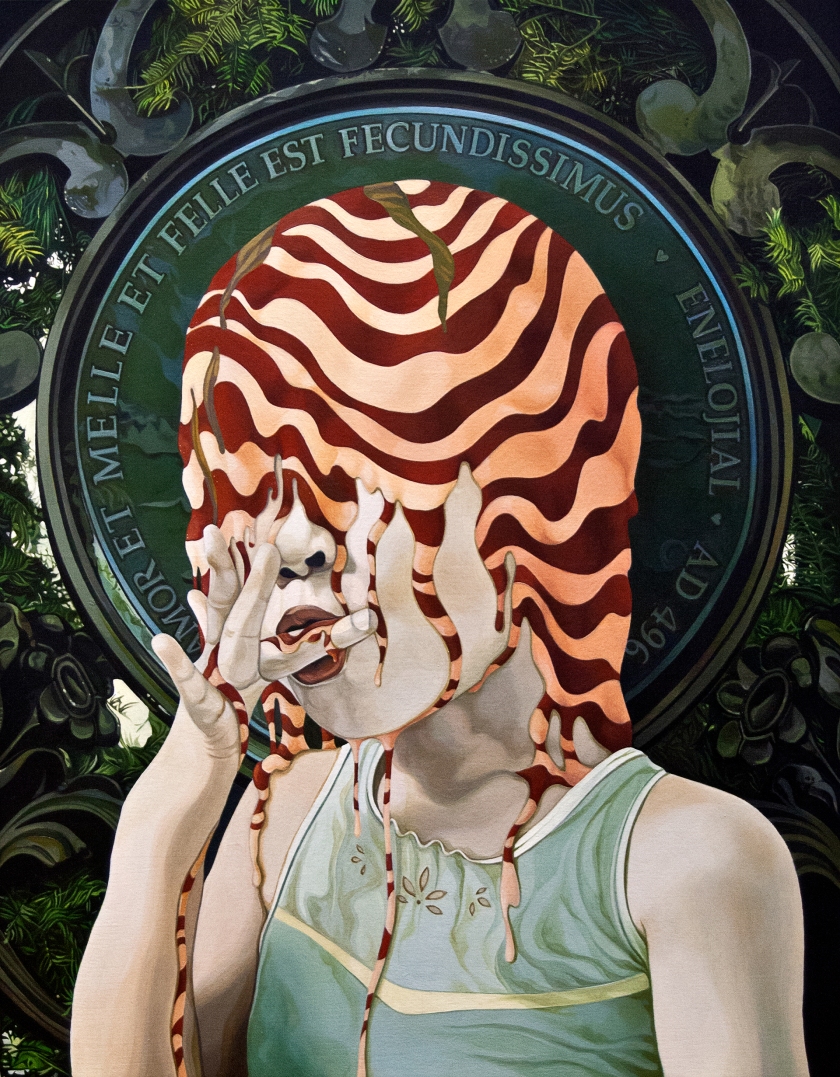

Jolene Lai has her third solo exhibition with the gallery, Beside You. Known for her narrative paintings in which characters are caught somewhere between dream and dread, Lai reimagines archetypal stories drawn from myth, Chinese folklore, and fairytale and transforms them into surreal compositions. By combining the uncanny with familiar scenes and contexts from the every day, Lai arrests our imaginations in a state of suspended disbelief. Her world is full of contrasts, extended metaphors, disorienting manifestations of fantasy, and hallucinatory dreamscapes weaved into otherwise familiar settings. In Beside You, Lai explores a progression of childhood scenes gone strangely awry, where the imagery is both whimsical and increasingly phobic. The playful naiveté of the children’s story ebbs into an ever encroaching sense of darkness and ends, entangled, in shadowy linings.

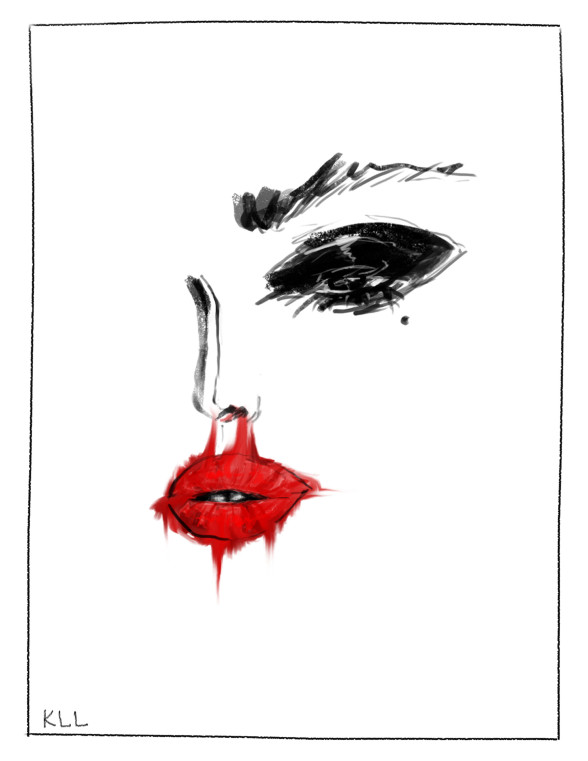

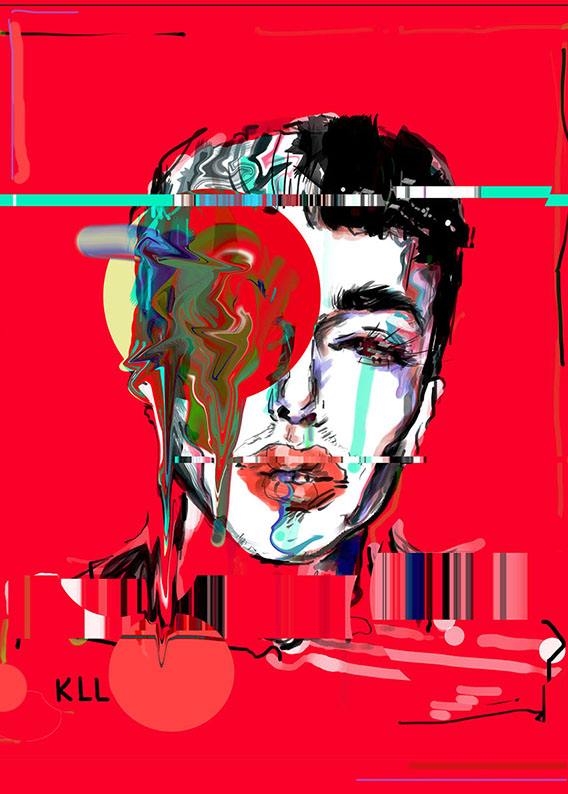

Watercolour, acrylic, missing eyes, and raw talent. Meet Kamile Lukosiute, who goes by the alias, KLL, a young illustrator from Lithuania, with an eye so sickening, you wouldn’t believe she’s only 18 years old.

This street art, fashion illustration cross-bred hybrid works of art, are sure to make you wonder what’s going on in her head, and maybe even your own. Vibrant colours, seductive subjects, and a hell of a lot of attitudes, KLL really brings a mood and message to her pieces.

Ute Rathmann is inspired by old masters such as Klimt, Schiele, Toulouse-Lautrec and Goya, this graduate of the Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weissensee works from life models, dressing her subjects according to a particular theme, in order to explore the human body and how it relates to clothes, costume, fashion and fabric.”

At 101 years old, abstract painter Carmen Herrera is beyond over the art world’s misogynist double standards.

The prolific artist, whose work is currently on view in New York at The Whitney, didn’t sell her first painting until she was 89 years old, in part a consequence of an artistic climate that underestimated and overlooked women. Nonetheless, she’s worked in a minimal yet incisive style since the 1940s, creating combinations of sharp-edged forms that overlap and intermingle. Most of her paintings feature only two or three colors, taking the shapes of triangles, rectangles and ovals that vibrate at the seams.

In the mid-20th century, Herrera has recalled, it was difficult for any woman artist to make a name for herself ― and nearly impossible for one whose work registered as stylistically masculine. Herrera, whose work was reminiscent of artists like Ellsworth Kelly and Ad Reinhardt, fell into this category.

In a recent interview with The Guardian’s Simon Hattenstone, Herrera recalled a particular conversation with avant-garde gallery owner Rose Fried, who gave a succinct and wholly infuriating explanation for why, despite her abundant talent, Herrera couldn’t land herself a show.

“She said, ‘You know, Carmen, you can paint rings around the men artists I have, but I’m not going to give you a show because you’re a woman,’” Herrera recalled. “I felt as if someone had slapped me on the face. I felt for the first time what discrimination was. It’s a terrible thing. I just walked out.”

Fried apparently went on to explain that male artists were in greater need of exhibitions because they had families to support, reasoning Herrera called out as a “lame excuse.” As to whether or not anyone had a right to know why Herrera didn’t have a family to support herself? “That is my business, not yours,” she told Fried.

Despite the misogynistic habits of the art world she was enmeshed in, Herrera kept painting. Today, around 70 years later, despite using a wheelchair and being arthritic, Herrera is still creating work.

And finally, although it took far, far too long, Herrera is receiving the artistic acclaim she’s long deserved. As The New York Times’ Holland Cotter wrote, Herrera is “finally getting the show the art world should have given her 40 or 50 years ago.”

Yet, even now, the art world has far from outgrown its gender biases. While Herrera has finally scored a retrospective, its scope pales in comparison to other exhibitions by men recently on view.

“Why didn’t the Whitney give Ms. Herrera not just the show she ought to have received some decades ago, but also the show that she deserves today?” Cotter asked. “Meaning a full retrospective on the big stage of the fifth floor, like those the museum bestowed on Frank Stella last fall, or even a slightly more focused look at her oeuvre from maturity on, as in the Stuart Davis survey that’s now in its final weeks. Well-intentioned as it is, ‘Lines of Sight’ gives us just a narrow slice of a career that’s seven decades strong and still going.”

It is clear that there is still much work to be done in terms of gender parity in the creative realm, but Herrera’s resilient style and determined spirit serve as an example of what is possible with hard work and a fierce antipathy for sexism.

Go see Herrera’s “Lines of Sight” before it closes on January 9, 2017 at The Whitney.

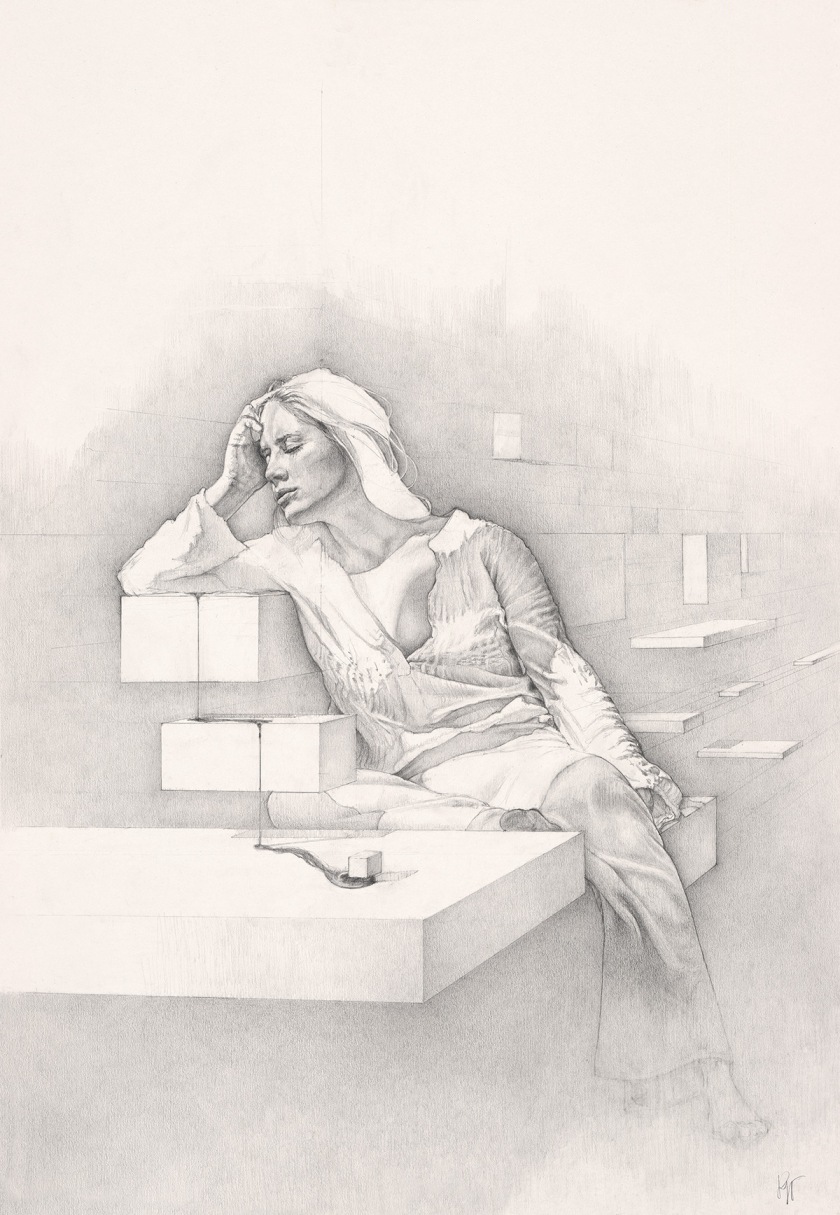

The Dutch artist Daan Noppen lives and works in Amsterdam but he represents the international art mainstream. He is well known for his realistic larger than life drawings of portraits and bodies. A closer look at his artworks will reveal mathematic equations in between the pencil strokes that relate to our reality. He creates a parallel reality of all moments that we normally cannot see with naked eye.

Go inside and beyond Dali’s painting Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus and explore the world of the Surrealist master like never before in this mesmerising 360° video.

Lesson of the day: How much do you know about these art pieces?

Mona Lisa:

Mona Lisa is a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo Da Vinci, which has been described as “the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world”.

The painting is a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Francesco del Giocondo, and is in oil on a white Lombardy poplar panel, and is believed to have been painted between 1503 and 1506. Leonardo may have continued working on it as late as 1517. It was acquired by King Francis I of France and is now the property of the French Republic, on permanent display at the Louvre Museum in Paris since 1797.

The subject’s expression, which is frequently described as enigmatic, the monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism were novel qualities that have contributed to the continuing fascination and study of the work.

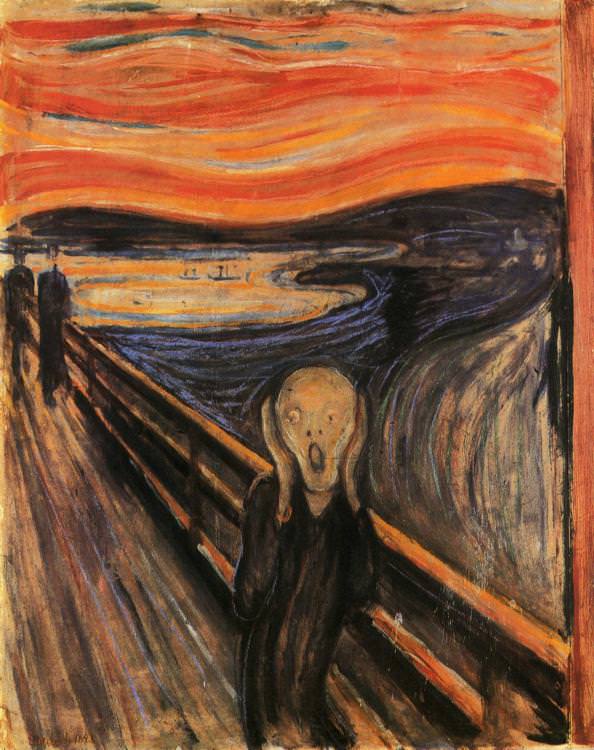

The Scream:

The Scream is the popular name given to each of four versions of a composition, created as both paintings and pastels, by the Expressionist artist Edvard Munch between 1893 and 1910. The German title Munch gave these works is Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature). The works show a figure with an agonized expression against a landscape with a tumultuous orange sky. Arthur Lubow has described The Scream as “an icon of modern art, a Mona Lisa for our time.”

Edvard Munch created the four versions in various media. The National Gallery, Oslo, holds one of two painted versions (1893, shown here). The Munch Museum holds the other painted version (1910, see gallery, below) and a pastel version from 1893. These three versions have not traveled for years.

The fourth version (pastel, 1895) was sold for $119,922,600 at Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art auction on 2 May 2012 to financier Leon Black, the fourth highest nominal price paid for a painting at auction.[5] The painting was on display in the Museum of Modern Art in New York from October 2012 to April 2013.

Also in 1895, Munch created a lithograph stone of the image. Of the lithograph prints produced by Munch, several examples survive.[6] Only approximately four dozen prints were made before the original stone was resurfaced by the printer in Munch’s absence.

The Scream has been the target of several high-profile art thefts. In 1994, the version in the National Gallery was stolen. It was recovered several months later. In 2004, both The Scream and Madonna were stolen from the Munch Museum, and were both recovered two years later.

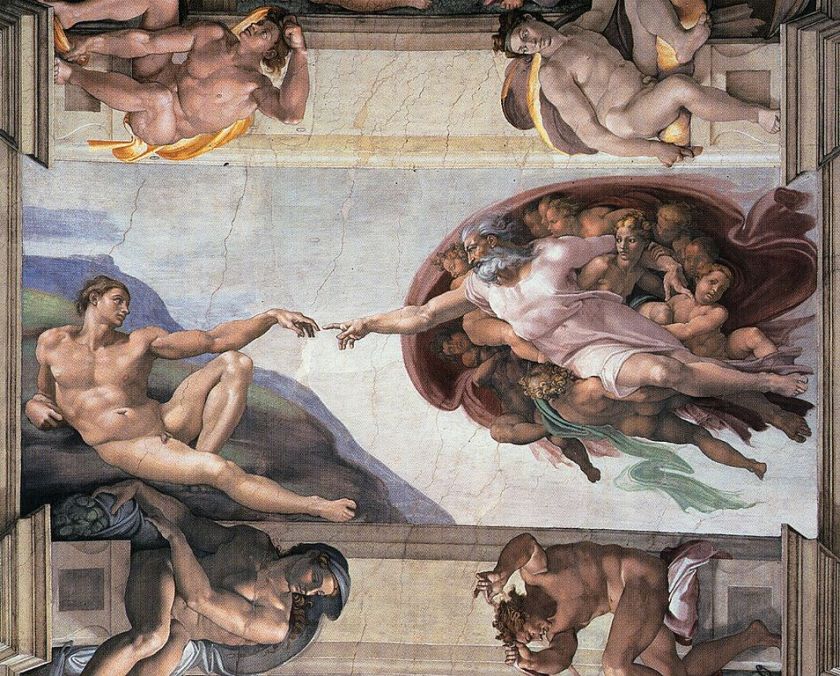

The Creation of Adam:

The Creation of Adam is a fresco painting by Michelangelo, which forms part of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling, painted c. 1508–1512. It illustrates the Biblical creation narrative from the Book of Genesis in which God breathes life into Adam, the first man. The fresco is part of a complex iconographic scheme and is chronologically the fourth in the series of panels depicting episodes from Genesis.

The image of the near-touching hands of God and Adam has become iconic of humanity. The painting has been reproduced in countless imitations and parodies. Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper and Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam are the most replicated religious paintings of all time.

Whistler’s Mother:

The Whistler’s Mother is a painting in oils on canvas created by the American-born painter James McNeill Whistler in 1871. The subject of the painting is Whistler’s mother, Anna McNeill Whistler. The painting is 56.81 by 63.94 inches (144.3 cm × 162.4 cm), displayed in a frame of Whistler’s own design. It is exhibited in and held by the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, having been bought by the French state in 1891. It is one of the most famous works by an American artist outside the United States. It has been variously described as an American icon and a Victorian Mona Lisa.

Imagine—as you probably do now and again—that you are God, laboring under the self-appointed task of creating an Eve who will be accounted beautiful at all times and places. History shows you will be disappointed in your effort. Rather than a stable set of features, physical beauty is an ever-morphing construct, a fickle collective dream that we fall into once in a while.

But as slippery as our fleshly aspirations may be, they tend nevertheless to have outlines. These have been most visible throughout history in the pictures drawn by those self-elected gods we call artists. History provides us a record, and from it one basic, inescapable, and ultimately unconscionable truth stands out: the ideals women are asked to embody, regardless of culture or continent, have been hammered out almost exclusively by men. This fact, more than any sort of evolutionary determinism, has meant that a fairly narrow range of attributes resurfaces across eras, returning every couple of decades or so like a new strain of the flu.

Physical ideals are changeable, manifestations of the cultures they come from, yet some aspects change more readily than others. Even when produced by those of their own gender, images of women have historically followed a pattern set down by males. Little about Artemisia Gentileschi’s Sleeping Venus (1625-1630), for example, suggests its female maker. In it, as in virtually all pictures of women, passivity is the norm, whether manifested as softness, slack musculature, or a deferential pose. Another abiding trait, the outline of the hourglass, reminds us that the Female is always a sort of clock, which we try to freeze at the moment of youth.

Still, in recent years the forces shaping ideals of feminine physical beauty have shifted markedly. The most notable of them is that, as part of a more general democratization of image consumption and production, women themselves began redefining the ideals to which they aspire. This means that many more notions of beauty are now available. Consider, for instance, the ways that figure shaping has altered over the centuries. Some 150 years ago, women in Europe began wearing bustles beneath their dresses that greatly enlarged the profile of their buttocks. The bustle had replaced hoop stays, which had produced an inverted-goblet figure.

More recently, the notion of sculpting has been applied directly to the body. In the 1960s, it took the form of dieting, which produced the sort of extremely skinny figure we associate with such models as Twiggy. Her thinness connoted vitality, an escape from the matronhood idealized by earlier generations, as well as an innocent, insouciant sexuality that was not dissimilar to a Roman-era depiction of the Three Graces. Consumerism, of which diet fads are certainly a part, has significantly expanded the range of off-the-shelf options for bodily enhancement. In the 1980s and ’90s, women frequently turned to surgery—breast or buttocks augmentation, nose jobs—and other non-surgical interventions (Botox, tanning).

It bears noting that if art holds a mirror up to culture, it has with rare exception failed to reflect a manifestation of female beauty of the last decade, one imagined into being by women themselves: the high-performance, muscled athlete. Popular magazines like ESPN The Magazine’s “Body Issue” have made gestures in this direction, by putting women like Serena Williams on the cover. But, in large part, art seems not to have taken account of the fact that the athlete has become a figure of everyday life, not just a pro.

However, if the following tour tells us anything it is that resistance is futile: we as a society, be it global or national, will always concoct versions of perfection—and aspire to remake ourselves in their image.

Egypt, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, Queen Nefertiti, ca. 1350 B.C.

The kohl around Nefertiti’s eyes and her apparently rouged lips speak to a desire for enhancement and adornment that seems too much a part of being human to have a historical starting point. Trends in altering how we look through fashion and jewelry in all likelihood predates any culture-wide preference for a specific body type. The Egyptian example has proven especially influential in the West, particularly since the 1920s.

Praxiteles, Aphrodite of Knidos, ca. 350 B.C.E.

Originally carved by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles around 350 B.C.E., the Aphrodite exists only in copies. Of which there were many, because this Aphrodite represented the embodiment of female beauty for Classical Greeks. For us, she is the original Western model, woman as goddess, to be adored and feared. Her soft, rounded flesh bespeaks the power of her sexuality and advertises her life-giving potential.

Bikini Girls, 4th century C.E.

Part of a mosaic found in the early 4th-century Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily, the “Bikini Girls,” as they are known, provide one of the few celebrations of the female figure performing athletic acts, other than dance, in the history of art. Thin without being wrought by exercise, their vivacious bodies would not be out of place in mid-20th century Italy or America. Which is to say, the present a “natural” ideal, formed by activity rather than training.

India, Tamil Nadu, Chola period (880-1279), Parvati, early 11th century

Consort of Shiva, Parvati is typically endowed with wide hips, ample breasts, and full lips. But, though hers is a more overt sensuality than the Western Venus, it is also not leisurely; her physique is not padded. She is active, essentially a dancer, with condign grace and strength.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Les Trois Grâces (The Three Graces), 1531

A theme from classical mythology, The Three Graces explicitly represented the ideal of feminine beauty. What that meant in the northern Renaissance was women of leisure—and little exercise—with thin, sinuous, and softly rounded physiques. Although these women bodied forth sensuousness, their figures, with relatively small breasts and depilated pubis, seem almost unsexed.

François Boucher, The Bath of Venus, 1751

The mythological trappings here are mostly a pretext. Formed by leisure—abundant food and non-strenuous recreation resulting in generous curves—the ideal rococo body is characterized by its colors. Blushing cheeks, red lips, and pearly skin at once indicate vitality and ornament the flesh, hinting at a playful sexuality.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Night (La Nuit), 1883

Far more than the avant-garde Impressionists, the salon-painter Bouguereau reflects the middle-class tastes of late 19th-century Europe. Woman here is allegorized as Night, a somewhat tamed temptress—her shorn pubic hair reflects prudishness rather than fashion, while her ample, hour-glass figure suggests fecundity as much as sexuality.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1981

When Mapplethorpe turned his lens on the winner of the first Women’s World Pro Bodybuilding Championship, in 1979, Lyon was considered wildly muscular for a woman. Today she wouldn’t stand out at your local gym. Yet, while she is presented as an exemplar of beauty, her musculature is a static enhancement, carved out like a statue, rather than something to be energetically employed.

David LaChapelle, Pamela Anderson: Miracle Tan, 2004

As the title suggests, Anderson’s is not a sun-tan but rather a spray- or bed-tan—purchased, not pursued in the outdoors. Such technological enhancements promise nothing short of the miraculous: her pumped-up breasts, machine-toned arms, and airbrushed skin all aim, in LaChapelle’s lens, to show that nature is but a poor imitation of artifice.

Bob Martin, Serena, 2004

More than any other woman, the tennis player Serena Williams has challenged—and redefined—norms of the female physique, allowing bigger bodies and developed muscles to compete in the aesthetic arena with the ideal of skinniness. Equally important: Williams’s muscles tend to be portrayed as built by and for athletic acts, not body sculpting.

Mickalene Thomas, A Little Taste Outside of Love, 2007

A contemporary version of the odalisque (which in art history has come to refer to almost any nude female reclining on her side but which, as in the title here, can also refer to a paramour). Sporting a “natural,” she recasts the artistic tradition’s most sophisticated sex object as a woman of African heritage. Thomas’s image exemplifies a recent embrace of a historically wider variety of female shapes—for instance, broad hips, a bigger booty, stronger thighs—as well as racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Heather Cassils, Becoming An Image Performance Still No. 4 (National Theater Studio, SPILL Festival, London), 2013

Cassils, one of the few contemporary artists to explore the aesthetic appeal of muscle, emphasizing its functional power. Here Cassils explicitly opposes a powerful body with raw clay: the artist performs, instead of posing. But, by questioning gender barriers as a trans artist, Cassils leaves stereotypes of female muscularity unchallenged.

Amalia Ulman, Instagram post (2014)

The mirror reflects not only social expectations for a young woman’s selfie—the thrust-out bottom, lingerie clinging to a thin, sporty figure—but also the power of her role playing. What has changed in the contemporary era is less her yoga-strung physique than the fact that she presents it for herself foremost and then allows the viewer access to her performance.

Daniel Kunitz / artsy.net

The ten best museums in the world chosen by the international travel agency Trip Advisor, according to the opinions of visitors, the Acropolis museum to be in the top ten and what specifically in ninth and fifth in the top of Europe.

Τα δέκα καλύτερα μουσεία του κόσμου επέλεξε ο διεθνές ταξιδιωτικός οργανισμός Trip Αdvisor, σύμφωνα με τις απόψεις των επισκεπτών του, με το μουσείο της Ακρόπολης να βρίσκεται στην πρώτη δεκάδα και ποιο συγκεκριμένα στην ένατη θέση και πέμπτο στα κορυφαία της Ευρώπης.

In the first area, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, followed by the Chicago Art Institute, the Hermitage Museum of St. Petersburg, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico.

Στην πρώτη θέση βρίσκεται το Μητροπολιτικό Μουσείο Τέχνης της Νέας Υόρκης , ενώ ακολουθούν το Ινστιτούτο Τέχνης του Σικάγο, το Μουσείο Ερμιτάζ της Αγίας Πετρούπολης, το Μουσείο Ορσέ στο Παρίσι και το Εθνικό Μουσείο Ανθρωπολογίας στο Μεξικό.

In sixth place is the museum The National 9/11 Memorial & Museum in New York and follows the Prado museum in Spain, the national British museum, the Acropolis museum and the Vasa Museum in Stockholm.

Στην έκτη θέση βρίσκεται το μουσείο The National 9/11 Memorial & Museum στη Νέα Υόρκη και ακολουθεί το μουσείο Πράδο στην Ισπανία, το εθνικό Βρετανικό μουσείο, το μουσείο Ακρόπολης και το μουσείο Vasa στην Στοκχόλμη.

You must be logged in to post a comment.